Admit something:

Everyone you see, you say to them,

“Love me.”

Of course you do not do this out loud,

Otherwise,

Someone would call the cops.

Still though, think about this,

This great pull in us to connect.

Why not become the one

Who lives with a full moon in each eye

That is always saying

With that sweet moon

Language,

What every other eye in this world

Is dying to

Hear?

-Hafez, “With That Moon Language”

Two summers ago, I had a creative writing class where only a few students wanted to share their work. The atmosphere in the classroom wasn’t helping out; although all of the students were in middle school, the more vocal students also happened to be the more sophisticated and socially-aware students, and their confidence intimidated the other students who hadn’t gotten there yet. Towards the end of the first week of our three week course, some students were starting to shut down, writing very little and stopping well short of what I’d consider a good effort from them. I was desperate to change the mood. After hearing the beginning of a powerful essay a student in another writing class wrote, I took the first line gave it to my students as the following writing prompt: “The thing you don’t get about me is ….” Nearly every student started in immediately, and most of them wrote for much longer than they had on any other previous assignment, well past the time when they would ordinarily go out for break.

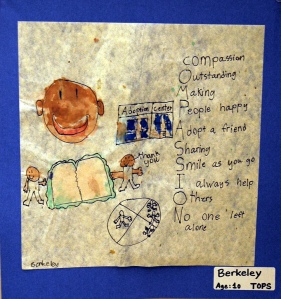

When the time arrived that we’d normally share the posts, I was anxious of how it would go, especially having already seen the personal nature of some of the essays. When I asked for volunteers, more of the class wanted to share than I anticipated. Some of them seemed even desperate to share. The essays they wrote talked about not feeling worthy of being in a camp for gifted students, about being teased for being the smartest kid in class, about the pressures they felt to succeed, about the confusing nature of friends who acted insensitively. Eventually, all of the students shared; most of the students wanted to read and needed little prompting. Those who were hesitant at the start received encouragement and support from their peers, and the more they heard stories of the struggles of their classmates, the more that they recognized this was a safe place where they could bring some of those things they felt embarrassed or confused about into the light. They saw the truth in Hafez’s command to “Admit something: everyone you see, you say to them, “Love me.” They felt exhilarated that his premonition that speaking from such a vulnerable place did not result in “someone call[ing] the cops.” The experience was its own reward. They loved the feeling of having these experiences exposed to the open air and the acceptance they felt when others did not judge them. The exercise changed the feel of the class. I was so proud, not only for the courage they showed, but also because they treated their classmates with empathy. More than that, they acted with compassion. As a teacher, I possess no tool more powerful than compassion. Mother Teresa said, “If we have no peace, it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other.” To me, that means that we forget how to act with compassion. In the first of these reflective posts, I discussed persistence and its dependence upon grit, the passionate pursuit of a goal. I spoke about how at the root of passion is the word patī, from the Latin verb meaning to suffer. In understanding what a passionate pursuit looks like, knowing this root is helpful because we see that someone who has grit is willing to suffer the setbacks that come with putting a wholehearted effort into chasing a dream without too much damage to the motivation that drives them. To extend these terms, compassion is a willingness to suffer with someone. It is greater than empathy because of the commitment and connection that it forms. Compassion is a recognition that your suffering is mine. It is a rediscovering that we belong to one another, and that can form great bonds.

Here’s why compassion matters to me as a teacher. It is the best weapon we have against shame. In the fourth installment in this series, I talked about shame, and the negative effect it can have on motivation, eroding drive and sapping the spirit. Going back to the Brené Brown talk that I referenced, we find that “shame needs three things to grow exponentially: secrecy, silence, and judgment.” As we grow older, we learn to anticipate what will bring a harsher judgment, and we tuck those thoughts, experiences, and actions away so that they never see the light of day. When shuffled away into the dark corners of our mind, years of rumination provide the appropriate self condemnation for it to become a part of our personalities. Yet if we act with compassion and live a life as free from judgment as possible, we open up the possibility for connection and provide the opportunity for what is shameful to come to light. As happened in my summer class, when we pull those thoughts out and expose them to the open air, they lose their power, and even if that is a momentary experience, it provides a supercharge to our motivation and a path to a richer life. As a teacher of writing, I wouldn’t recommend sitting down with any student and asking outright, “Tell me what you are shameful about so I can practice compassion.” However, some amazing things happen when we can create an environment feel safe enough for writers to connect in a deeper way.

The students who were willing to share parts of themselves in their writing during all of my summer classes had a powerful effect on me, and I was sad to see each them go at the end of the class. The college students whom I work with throughout the school year are often harder to get to open up in the same way. Many of them have become so adept at judging themselves and their own actions that they have developed greater defenses than my middle school students. Many times, these defenses appear in the form of prejudgments they make about themselves. College students are much more likely to come to me and tell me that they are doing poorly because they are just bad at writing. My first strategy here is to forbid them saying that. They can say that they are not good at writing, but they have to add a “yet” to the end of it. This, as you can imagine, provokes a lot of eye rolling. I don’t mind, and in truth, I don’t intend for it to change anyone’s mind. What I hope it does though is start the process of becoming better. I want to show them that I’d rather sound incredibly corny than hear them put limits in place before they ever start working at improving their writing. My hope is that it opens them up to the true purpose, which is to start attacking whatever shame they’ve felt weigh down their minds and sap their motivation.

I once heard a college student describe her choice of major as a process of elimination. She originally wanted to be a doctor, but she did poorly in the first class she took in the premed track. She determined she was bad at that subject, so she switched to another major. After doing poorly in a class within the new subject, she determined she was bad at that too, so she changed majors again. A third time, she tried a new major and her poor performance convinced her again that she was unsuited to follow that path. I don’t know where that student is now, but I worried about her at the time. She was crossing off paths so quickly, I feared she’d be left with no way forward. I can’t hear that student’s comments without thinking her shame defenses were in overdrive. Those walls blinded her. She missed the fact that if college wasn’t hard, the degree would be worthless. Too many of my students don’t get that. They gravitate towards the path of least resistance because they are afraid to fail.

To get past that fear, they must start showing compassion for themselves and their own limitations, but that is an extremely difficult process. Understanding the difficulty of this obstacle has directed a lot of my research over the past few years. The source I’ve found the most inspiring has been Father Greg Boyle’s Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion. The book is a memoir, in which Boyle tells stories of his time serving at Dolores Mission Church in the poorest parish in the archdiocese and the highest area of gang concentration in Los Angeles, the gang capital of the United States. When Boyle arrived in 1984, he felt responsible for trying to do something about the gang problem. He rode his bicycle around the projects at night and met with gang members trying to broker peace treaties between them. He stopped these methods shortly afterwards when he saw that the brief armistices only served to provide legitimacy to the gangs. Boyle saw that if he wanted to do something about the gang problem, he needed to change the circumstances that led young people join the gangs in the first place.

Boyle recognized the role shame plays in fueling the gang addiction. In describing the mental state of the homies he works with (he uses the former gang members own words word “homeboys” or “homies” to imply the kinship they share), Boyle writes, “There is a palpable sense of disgrace strapped like an oxygen tank onto the back of every homie I know. This is hard to get through and penetrate.” He confronts a young boy for missing class, and the boy protests, “I don’t got that much clothes.” The boy had “so internalized the fact that he didn’t have clean clothes (or enough of them) that it infected his very sense of self.”

To combat shame, Boyle wanted to offer jobs gang members who wanted to change. However, many of them weren’t trained to do anything and were ill fits in the modern workplace, so in 1992, Boyle worked with a patron who wanted to help to purchase a bakery near the church, and Homeboy Bakery was born. Since then, the venture has expanded into Homeboy Industries, which now includes a café, diner, farmer’s market, and screen printing business among other businesses. Currently, it is the largest gang intervention program in the nation.

The bottom line for Boyle is that former gang members work and participate in the program until “the soul feels its worth.” Along with the opportunity to work, Homeboy Industries provides free tattoo removal for gang members who want to erase the visual marks of their past gang life. The mental and emotional marks are deeper and harder to erase. Boyle understands that in order to move forward, the messages of shame that drove them to gang life have to be counteracted. For that purpose, Homeboy Industry provides education classes and counseling dealing with a range of issues, including cases of substance abuse, domestic violence, and underlying attachment issues that drove many of the gang members towards that life in the first place.

Father Boyle is a wonderful storyteller, so I won’t try to replicate his stories here, knowing that he’s better experienced in his own words. He’s done enough talks that are on YouTube (here’s a good starting place) that you can find your own inspiration. He is a Christian, a Jesuit Catholic priest, and I know that promotes skepticism in some, but if that’s your only objection, go into the experience fully skeptical. You’ll still be moved.

The soul feels its worth. I can’t think of any better description of the power an education can offer. I don’t work with gang members, so relative to Boyle, I have chosen the much easier path. The students I work with are generally coming from stable households or have supports in place that have allowed them to reach a level of achievement necessary for them to come to a point of attending a selective school. Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean it’s easier to get them to see their worthiness; it only means that their issues of shame are less obvious. For most, it’s some manifestation of a fear of failure or a fear of isolation. It is a fear that they will not live up to the image they or others have of themselves and possibly a fear that even living up to whatever that image is will not be enough.

The poem from Hafez that I’ve started this post with closes the introduction to Boyle’s book. The Mother Teresa quote above also appears later in the book. They appeal to me because they speak to the vocation that moves me to teach. To them, I’ll add another that came along at the right time of my life and which I’ve carried with me since. In Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, the main character attempts to come to terms with a grief that is challenged by a lack of understanding of the deceased. He concludes that “you can love completely without complete understanding.” The possibility that compassion can be boundless is a challenge that drives me and at the same time intimidates me. The possibilities that one might be “the one that is always saying what every eye in this world is dying to hear” or live with the remembrance that we belong to each other are goals that I’d like to say I’ve been trying to reach for the past five years, but still I fear that declaring them as such opens me up to failure. I know that they are not goals that are never truly reached. I can only try to keep them as principles to follow for the rest of my career.

For now, more than anything else I have done, being a compassionate teacher means being present, totally present, when I speak to students. It means understanding that they didn’t come into the Writing Studio as a piece of clay ready to be formed. Many of them need a bit more work before they can approach feeling their own worth, but when a student approaches that it is hard not to feel a glowing pride, knowing that I could play a part.

This post concludes the five-year reflection series, and possibly just in time as they have become increasingly more philosophical and sentimental than I had originally intended. If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading.

Excellent web site you’ve got here.. It’s difficult to find good quality writing like yours these days.

I truly appreciate people like you! Take care!!